Website by Karen S. Franklin

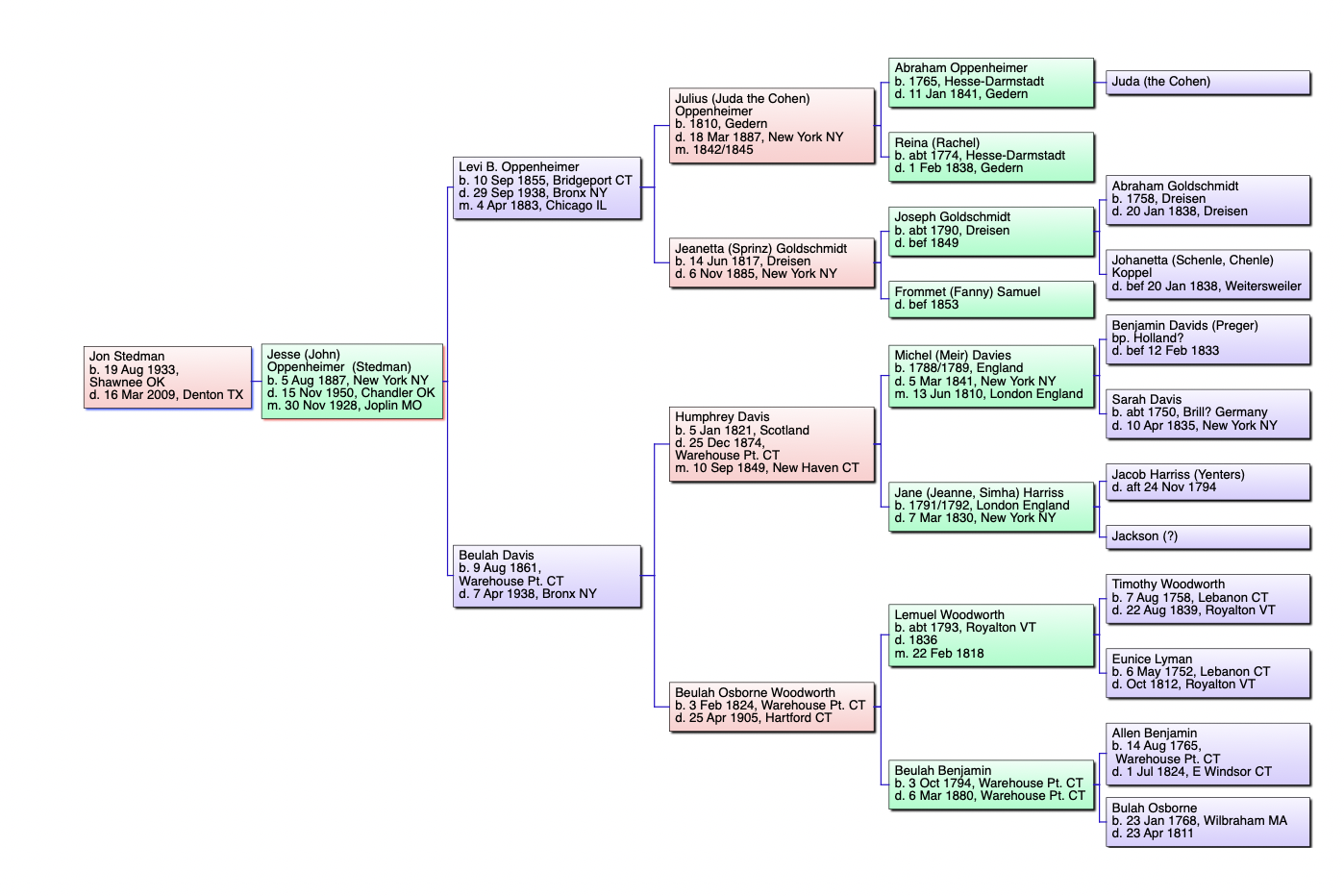

Jon Stedman Family Tree

Jon Stedman & His Legacy

Jon Stedman was born in Shawnee, Oklahoma in 1933. As a young man he worked for some time in Washington, DC as an accountant. But his passion was genealogy. He had a persistent and dogged interest in tracing his family history: his mother’s and father’s ancestry, and well beyond. He worked on this consuming project for over 50 years, well before the information he sought was easily and instantly available online.

Jon was a modest man, devoted to his mother, and lived with her for some time in Denton, Texas, where he died in 2009. Stedman spent a great deal of time in the Denton Public Library, where he was well known for sharing his expertise with other researchers. True to his passion, he left his estate to organizations that would help other genealogists.

The Collection

Jon left an enormous uncatalogued collection of his papers based on his 50 years of research. In July 2012, I was hired to organize his papers and make public his Jewish ancestry. This was a large task indeed and he left no specific instructions with the executrix of his estate, Holly Hervey, or with Dayonne Work, a colleague who organized the collection and oversaw its care.

The collection represents but a portion of Jon’s research. Research papers for non-Jewish branches of his family were directed to other archives.

The collection arrived at my office in two forms: four disks of scanned materials, and several boxes of files. Most of the “files” were in envelopes, painstakingly prepared by Dayonne and Jon.

Denton Public Library

The Denton Public Library is where Jon researched and assisted other patrons.

The Collection Arrives

The collection arrives at my office in August of 2012.

The Collection is Organized

The collection is initially organized, letters opened, and fragile documents encapsulated.

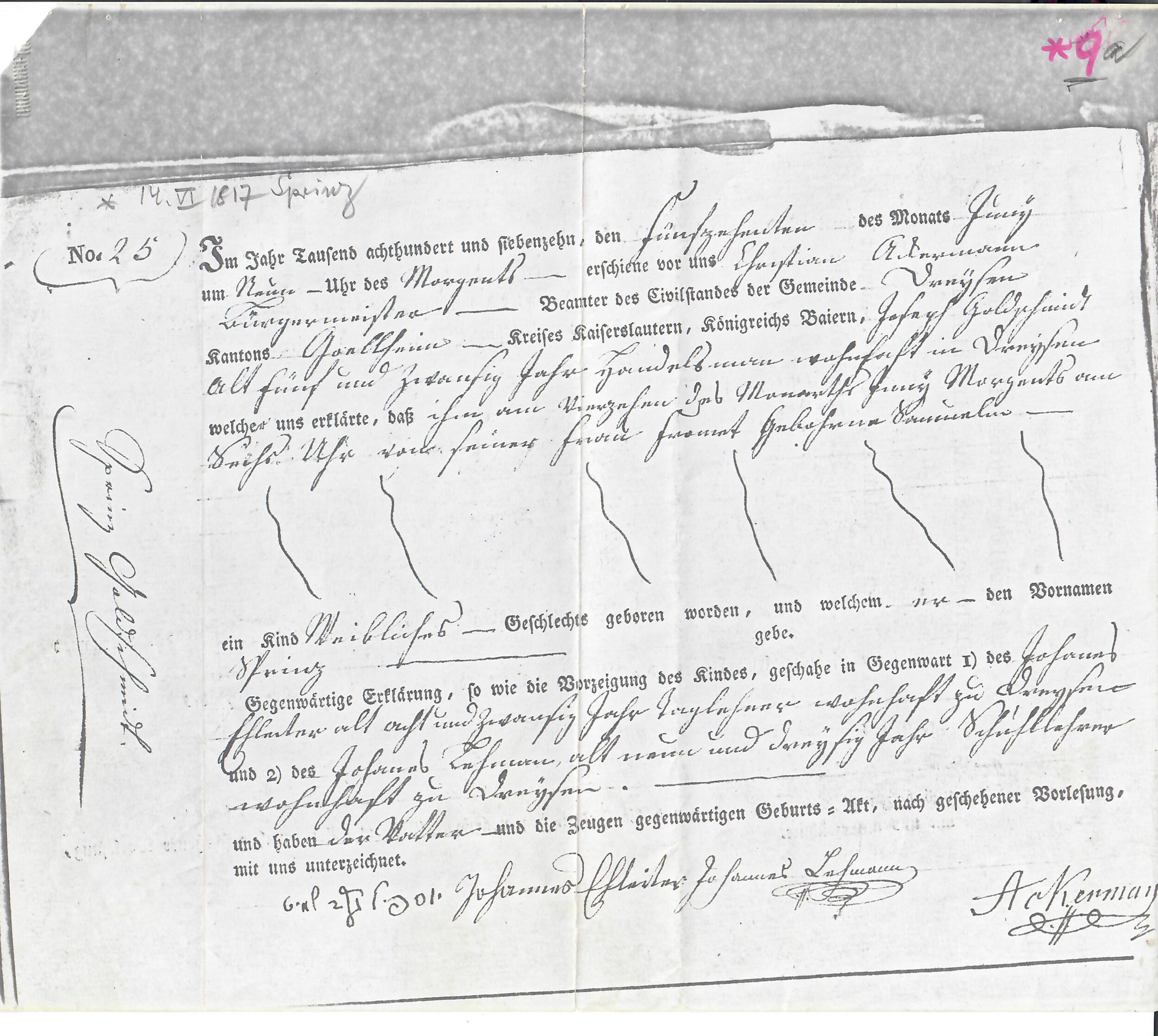

I selected the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, Ohio as a repository for the Jewish material. Jon had already deposited copies of his work at the Archives and established a relationship with the staff there. He had an extended correspondence with Rabbi Malcolm Stern, the Archives’ genealogist, author and editor of First American Jewish Families: Six Hundred Genealogies 1654 – 1988. Jon prepared complete trees of several families: The Goldschmidt/Oppenheimers, Davis and he added branches to others. This research was completed prior to publication in the early 1970s, and for updated editions in the following years.

The American Jewish Archives digitized First American Jewish Families. The trees are searchable on Google or on the American Jewish Archives web site at www.americanjewisharchives.org.

Jon Stedman & his Mother

Jon Stedman and his mother.

Jon’s Initial research

The first evidence of Jon’s quest to find his family is a 1958 inquiry to the Department of Health in New York City to obtain the birth record of his grandfather, Levi Oppenheimer, born on August 5, 1887. It would be the beginning of a half-century of research that lasted to his death in 2009.

At the time Jon began, the cost of obtaining a vital record was $1.00, and the cost of a stamp $.05. He dedicated much of his income to his research costs. We know this because when Jon moved to Washington DC, his mother wrote him (on the back of a family newsletter) “I am going to include a check for $10 which will help you to eat at least one good meal a week, so on Sundays at least stay off McDonalds and Kentucky Colonels.” February 1, 1972. (Or perhaps he just liked bad food.)

In these years, records were onerous to obtain. In 1970, when Jon requested a copy of the 1900 census, it was available only if the person who requested it was a parent, grandchild, child, husband, wife, brother, or sister of the deceased (and several other categories, according a response to a request by Jon Stedman by the U. S. Department of Commerce, Department of the Census in Pittsburg, Kansas). Today much of this material is available to anyone and online.

Jon’s collection includes not only copies of records but also original documents.

Sallie Ardath Tolson Stedman

Among the research papers are many that bear the handwriting of Sallie Ardath Tolson Stedman, Jon’s mother. The conversations they had about the research are not recorded, but the notes she took that pepper the files.

According to friends, Jon was devoted to his mother. Born in 1902 in Jaky, Johnson, Oklahoma, she passed away in Denton Texas on January 13, 1984. Though this site deals with the roots of three of four of Jon’s paternal great-grandparents (a non-Jewish branch is not included), Jon’s mother obviously had some familiarity with them.

Sallie was the daughter of Thomas Tolson, born Shelby, llinois, and Emma Cole, born in Fannin County, Georgia. The couple married in Tecumseh, Oklahoma. Sallie’s mother’s family, Harris and Cole, came from Georgia and North Carolina. Jon’s mother published a book about her branch of the family, and research material may be found in the Denton, Texas Public Library and elsewhere.

The extensive documentation on CDs comprises material on the Oppenheimer and Goldschmidt lines of his family as well as non-Jewish branches. Several are followed in more detail: Goldsmith, Beebe, Oppenheimer, and Prentice. The collection as it is can be of value as an example of the methodology of a genealogist in the second half of the 20th century.

Many of the documents are merely notes on other sources, census record extracts, and letters from archives documenting that they couldn’t find copies of vital records. Entire files are comprised of vital records and notes for unrelated families.

We could find few files of research from the years 1975 to the early 1990s. Perhaps Jon was working on his mother’s non-Jewish family at this time. In the 1990s he returned to the task of tracking down and updating various branches of the trees. With the advent of internet communication, DNA, and other genealogy resources, Jon plowed into the hunt again.

Jon’s files are remarkable for the trail they leave in how he educated himself on the latest techniques and methods of research. He did so by correspondence with various experts in the field, by collecting articles about methodology, and contacting a number of genealogists whom he found on the Jewish genealogy web site JewishGen.org. Many of these individuals had an interest in the same family names. In the end, some proved not to be related, but for those where there was a connection, Jon’s trees were enriched greatly.

Types of documents

The files included vital records, obituaries and newspaper clippings, and social security records. Jon wrote to many cemeteries to inquire about burials, and he collected maps identifying plots of the deceased. It is not known whether he actually visited those plots.

He was assisted by librarians, historians, researchers in other countries and funeral homes. He consulted local histories published in Germany, Holocaust databases and books, city directories, and encyclopedias. He employed researchers in England, Germany and cities throughout the United States.

Military pensions records were a favorite source, and we find many, not only from the Civil War, but also from the Spanish American War.

He also referenced wills, surrogate court papers and naturalization documents. He wrote to institutions including Congregation Beth El in Fort Worth, Texas, the American Jewish Historical Society the Museum of the City of New York, and the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience. He consulted minute books of organizations.

The files include correspondence with the editors of Who’s Who types of directories. He contacted his local congressman’s office, as well as the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Railroad Retirement Board was another recipient of his requests.

He used the International Tracing Service for Holocaust Research in Arolsen, Germany https://arolsen-archives.org, as well as Paul Arnsberg book entitled Die jüdischen Gemeinden in Hessen. Anfang – Untergang – Neubeginn. He assembled photographs of some branches of the family.

Sample Family Page

There are hundreds in the files.

American Jewish Archives

Six months into the research, I visited the American Jewish Archives. Jon had donated some of his collection there already. I was curious to know why a portion of the collection had been donated to AJA, some of that research as early as 1971. Upon seeing it I laughed. Four giant folders greeted me, looking surprisingly similar to the ones I had unpacked months earlier – folded papers of faded penciled notes, folded vital records, letters to the American Jewish Archives and other organizations. But why did Jon send these files to the Archives? After some perusal I realized that these research files had been discarded by Jon after additional study showed that the families were unrelated to him. Surely Jon thought that they would be of interest to other family historians.

Unfortunately, the archives did not have the resources in 1971 to further process and identify files by the family names (Oppenheimer, Davis). Unless researchers know to check Jon’s collection, they may never know about these papers.

Methodology and Colleagues

Jon’s extensive correspondence about research methodology and potential relatives with other researchers is remarkable in many regards. It is a testimony to the generosity of the genealogical community and how much time they devoted to helping fellow family historians.

The records attest to the changes in the methodology of genealogical research. In the early years, Jon mostly accumulated vital records and family trees. By 1994, with the advent of the internet, he took advantage of the new technology to more efficiently research and correspond.

He sought and received assistance from genealogists, many of whom are still active in the field today:

John Lowens

Peter Lande

Meg Power

Ernest Kallmann in Paris (records in the Rheinland-Pfalz)

Dick Plotz

Rachel Unkefer

Michael Marx Reuven Mohr (Goldschmidt and Kohlman)

Bernard Kukatzki (regarding various Pfalz lines)

Ernest Stiefel (general questions and Gedern)

Peter Wyant (German naming practices)

Eileen Polakoff (hiring researchers)

Karen S. Franklin (this author, concerning the Leo Baeck Institute catalog online)

Sally Goodman (Scotland and Breitenstuhl)

Wolfgang Fritzche (Name adoption lists of Bodenheim)

Saul Issroff (copied general information)

Micheline Gutmann (Goldschmidt of Gruenstadt)

Sandy Bursten (Goldsmith branch of her family)

Michael Bernet (Goldschmidts)

Anthony Joseph (Davis family)

He wrote snail mail letters to Elizabeth Plaut, Teri Tillman, and Paula Zieselman.

Scholars he corresponded with included Dr. Bertram W. Korn, Dr. Jacob Rader Marcus, and Dr. Cecil Roth, the great British Jewish historian.

Father’s Story: How did Jesse Oppenheimer become John Stedman?

According to the original information I was told, Jesse Oppenheimer, later John Stedman, took the name of a John Stedman who had died, in an attempt to hide his original identity, and probably his Jewish identity as well.

Jesse Oppenheimer’s maternal aunt Elizabeth Davis was married to a Byron Stedman in Connecticut. Their youngest child was named John Stedman. Jon discovered pension records for a John Stedman who was born on July 8, 1876 in East Windsor Hill, Connecticut and died June 16, 1932 in San Francisco, California.

The 1926 declaration for pension filed by John Stedman born in Connecticut informs us that he had served in Alcala, Luzon, in the Philippines. The pension listed his incapacities as: impaired vision; deafness in right ear; a variety of issues including weakness of right ankle, weak kidneys and underweight.

Since Jesse knew of this cousin, he might have been able to have provided any family information that would have been required should his identity ever be questioned, and possibly John Stedman’s whereabouts were unknown to the family.

In 2006, Jon wrote a message about his father’s name change.

“Jane and Byron Stedman had a son John who had disappeared, so my father took his name when he did likewise. My half-brothers’ names were changed when they were young, to Palmer which was their maternal name.”

Jesse Oppenheimer was born just over a year after John Stedman’s death. When did Jesse Oppenheimer take on the new name?

John Stedman was a common enough name that he was able to use it with little fear of detection. The 1930 census lists 82 John Stedmans. The Stedman name goes back to the early 17th century in the United States. A John Stedman was born in 1632 in Hartford, Connecticut according to Ancestry’s One World Family Tree, and the Stedman name appears over 100,000 times in Ancestry trees (there may be many duplicates of the same trees, but the name is common).

Only much later were we able to determine the real reason for the name change.

Among the photographs in the files of Jon Stedman we find one that we can only assume was taken in about 1925 – a dashing Jesse Oppenheimer/John Stedman taken in the German town of Gedern, where his Oppenheimer ancestors came from.

Why did John Stedman return to Gedern? It would not have been to visit his grandparents, both of whom died prior to his birth in 1887. Of his grandfather’s siblings, only a few descendants remained in Germany. His father’s first cousin Wolf (whose grave we visited in November 2012) lived until 1929 in the town. But his father Levi was born in the United States in 1855 and Wolf in Germany in 1850, so they may have never met.

Jesse Oppenheimer

Later John Stedman

Oppenheimer Family in Gedern

In November 2012, I visited the community of Gedern in Hessen while in the area to give a lecture nearby.

Stedman had traced his father’s family, Oppenheimers, back to 1730 in Gedern. The people with whom Jon Stedman had corresponded in the 1960’s (as early as 1967) and 1970s were no longer associated with the town (most are deceased), or so we had been told. They had been historians and archivists in the regional archives, and individuals contracted to translate documents.

The documents were meticulously copied – photographed, most with excellent resolution, and also carefully translated.

Ketubbah

Ketubbah (marriage contract) between Loew Oppenheimer and Bina Kahn. The couple was married in Gedern on June 18, 1834. The ketubbah may have come from a German archive.

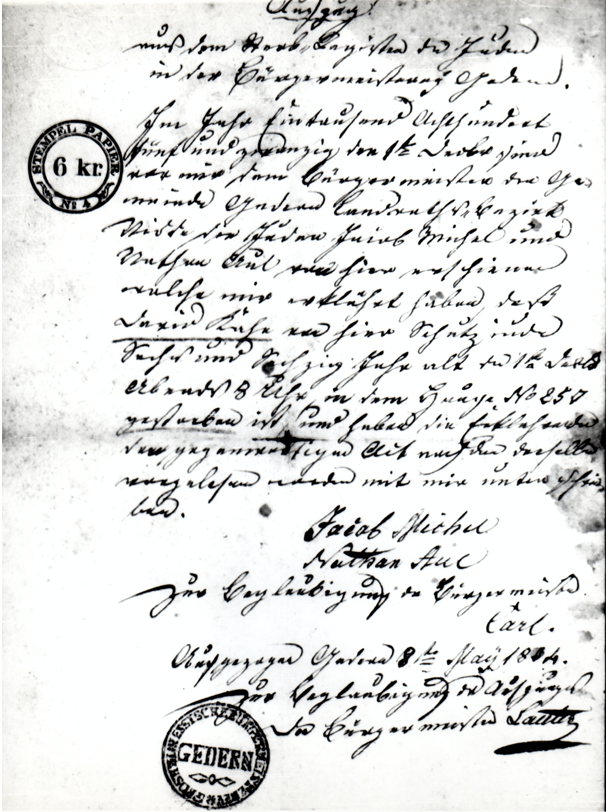

Translation

Extract: From the register of Jews in the mayor’s office in Gedern. In the year 1825… the Jews Jacob Michel and Nathan Aul from here appeared before me, the mayor of the town of Gedern, county Nidda, who told me that the protected Jew David Kahn from here has died at the age of 66 … at 8 o-clock at night in the House No. 257 and these two ? after being read the same have signed together with me. Jacob Michel, Nathan Aul, certified the mayor Carl. Extracted Gedern, March 8th 1834. The extracts have been certified by the Mayor Lauter.

It seems that in 1994 Jon had a renewed interest in the Gedern material, and corresponded with a well-known Jewish genealogist, Ernest Stiefel of Seattle, Washington, who was able to direct him to additional archival resources for the town. Ernest also had ancestors from Gedern and he described in a letter dated April 29, 1994, his own correspondence with a Herr Erwin Diel in Gedern. Diel did not reply to subsequent letters, and Ernest describes the town as “still a very anti-semitic place”.

It is a pity that the residents today know little about Gedern’s former Jewish community and had no knowledge of Jon’s extensive research. There were no local historians who knew in any detail of the history of the Jewish community.

The Former Synagogue in Gedern

The former Synagogue in Gedern, Monika Kingreen in foreground

I arrived with two friends who served as fine translators: Dorothee Lottmann-Kaeseler, formerly the director of the Jewish museum in Wiesbaden, and Monica Kingreen, a researcher from the Fritz Bauer Institute and recognized historian of Jewish history in Hessen. Monica had a great interest in the town, and already knew something of its Jewish history. We were met by Harald Warnat, a local contractor who serves as ad-hoc local historian, and Yvonne Reeker, a student, who also had an interest in the project.

We presented them with a complete copy of the family sheets prepared by Jon Stedman, copies of the extensive Oppenheimer trees from Malcolm Stern’s book, First American Jewish Families, which Stedman had prepared, and a memory stick that contained selected photos of the Oppenheimer family, including several individuals who were born in Gedern, copies of German 18th and 19th century documents from Gedern that Jon had collected many years ago, and selected documents from America from the Stedman files. We told Mr. Warnat and Ms. Reeker that the entire Stedman collection would eventually be digitized and available at the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, OH. Harald and Yvonne were delighted with the material, and promised to share it with their colleagues.

We were also greeted by the Vice-Mayor of the town, Mr. Schmidt, who presented us with a book about the local Jewish history written by Thomas W. Lummitsch, Juedisches Leben in Gedern. The book had been written in 1989 following an anti-Semitic incident. Stedman owned the volume, and referred to the book in one of his latter emails.

Stedman used this resource in his later research with Ernest Stiefel, but was stymied by its limitations. The book was not of good quality. The author had not traced the history of the community back as far as Stedman did. In fact, the documents Stedman found documents almost a century earlier than those included in the book.

The local representatives took us to the Jewish cemetery in Gedern. The tombstones had been overturned in 1938 and only recently reconstructed. They are not in the same order as they were before the war, but the cemetery seems to be kept up fairly well. There were quite a few Oppenheimers buried in Gedern, and we can connect them with Stedman’s family.

Jewish Cemetery in Gedern

Wolf Oppenheimer was a first cousin of Levi Oppenheimer, Jon Stedman’s grandfather. Wolf’s daughter, Pauline Stern, was murdered in the Holocaust. In 1973 Jon Stedman wrote to Karl Friedrich von Frank in Austria commissioning him to do additional research on Wolf.

Wolf Oppenheimer

Our local hosts and the vice-mayor were so excited to learn about Stedman’s research that they spoke about arranging an exhibition in the town. This did not happen.

I’m sure Jon Stedman would have been delighted to know that the Oppenheimer story he unearthed has been returned to Gedern.

Zilda (Cilta) Oppenheimer

Second wife of Wolf Oppenheimer.

Goldschmidt in Dreisen

Jon’s great-great-great-great grandparents were Hirsch Abraham Breitenstuhl and Karolina Hirsch, born in the mid 18th century in Weitersweiler, a small community in the Pfalz near Dreisen, where they later settled. Jon became interested in this branch a few years before his death in 2009, and corresponded with Breitenstuhl cousins Jed Brickner, Cheryl Hays, Sally Goodman and Yaron Zakay. By this time the Breitenstuhl descendants of Abraham and Karolina had been well documented and the trees posted on JewishGen.org’s Family Tree of the Jewish People, and likely elsewhere.

Yaron Zakay wrote Jon with an extensive theory and notes showing that Abraham Goldschmidt was one of three children of Hirsch Abraham Breitenstuhl and Karolina Hirsch. His ideas, “Evidence Regarding Hirsch Abraham (aka Hirsch Abraham Breitenstuhl) and Goella (aka Carolina Hirsch) of Weitersweiler, Bavaria and their Children” posited the relationship among three full siblings: a daughter, Schoenle, who married Isaac Weil; Abraham “I”, who was born in 1759 and died on January 22, 1838, ancestor of Jon; and a third son, Abraham “II”, who married Esther Guthenthal and was known as Abraham Breitenstuhl or Breitenstahl, a merchant of Altenglan.

Map of Weitersweiler, Germany

Holocaust Research

In the early 1970s and again in the mid-1990s, Jon contacted numerous archivists and archives in Germany to learn more about his relatives who perished in the Holocaust. Today some of this information may be found online, but it was not so simple at that time. He learned that several Oppenheimer and Goldschmidt cousins were murdered in Auschwitz.

The Davis Family in England and earliest American settlement.

By 1966, Jon Stedman was tracking down his English Harris, Prager and Davis ancestors. Some of the standard trees we take for granted today were created with Jon’s research.

Jon’s research was accomplished by writing extensively to individuals researching those same names, most of whom were not related. In addition to Harris and Davis, he was also trying to make a connection to the Hart and Jackson families.

From about 1970 to 1975, Jon employed Ronald D’arcy Hart, who searched through London probate, synagogue, city directories, and burial records. Hart was unable to confirm most of the Davis/Prager relationships, despite a great deal of legwork. Hart’s fee must have been onerous for Jon at this time in his life. The research was not only for direct ancestors, but also to connect other New York and American families to these British relations.

A great deal of attention was given to an exact translation of the specific documents, especially the marriage record from the New Synagogue in London for Michel (Meier) Davies and Jane Harris, for the names of their parents on this document were to be the only confirmation for the preceding generations.

Michel Davies

Michel Davies son of Binyamin Preger or Pregir, born in England in about 1788 married Simcha (Jane, Jeanne) Harris on June 13, 1810. Several scholars reviewed the Hebrew on the marriage document to interpret the spelling of the original names. The bride’s name was thought to be Simcha bat Yaakov Yenters, daughter of Jacob Harris (or Yenters/ Yentern or Yentorf).

Jon was able to trace the family to Jacob Harris, who was made a mason on November 24, 1793 in Lodge # 221 under the Grand Lodge of the Antients, and made a Master Mason on November 24, 1794, as per a parchment in the possession of Mrs. Edmund Herbert Levy at the time Jon prepared the family sheet. This document is of great interest.

When we began our research we knew little about this Antients (Ancient) Grand Lodge of England. Having more resources at hand than Jon had many years ago, we consulted with Saul Issroff, a leader of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain. He posted an inquiry and received several responses from individuals who had ancestors belonging to lodges in the 18th century, or who knew where to find more information. One led us to find an entire archive on the topic, the Library and Museum of Freemasonry in London. Their site listed not only an image of an apron (ritual vestment of the lodge) that was contemporaneous with Jacob Harris’s membership, but also an article by Jacob Katz that was available online in its entirety. http://themasonictrowel.com/ebooks/freemasonry/eb0142.pdf

The article, “Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939”, published by Harvard University Press in 1970, gives context to freemasonry in Germany, Holland, France and England, and can be consulted for a lengthy discussion of the topic.

The earliest Jewish Freemasons in both Holland and England were Sephardim. The participants in the Grand Lodge of London, mentioned above, included the Mendez, De Medina, De Costa, Alvares, and Baruch (the last named may possibly have been an Ashkenazi) families. Among the petitioners of 1759, such names appear as Jacub Moses, Lazars Levy, and Jacub Arons, all of whom may have been Ashkenazim. We know the exact text of a membership certificate, dated 1756, of a Jew, Emanuel Harris, a native of Halle, Germany, who had changed his name from Menachem Mendel Wolff. The text of this certificate was published in 1769 by the research scholar Olof Gerhard Tychsen, who mentioned as a commonly-known fact that in England, in contrast to Germany, Jews were admitted to the Masonic lodges as a matter of course. Tychsen was even able to relate that one of the affiliates of the Grand Lodge of London was referred to as "The Jewish Lodge" on account of the composition of its membership.

It is to our astonishing good luck that the one membership certificate published in 1769 by Tychsen, likely refers to the ancestor of Jon Stedman. Emanuel Harris, could very well have been the father of Jacob Harris(s). It is worth noting that Emanuel (Mendele) Harris, whom Jon suspected was Jane Harris’s brother, would have been named for him.

The Ancient Grand Lodge of England, as it is known today, or The Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honourable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (according to the Old Constitutions granted by His Royal Highness Prince Edwin, at York, Anno Domini nine hundred and twenty six, and in the year of Masonry four thousand nine hundred and twenty six) as they described themselves on their warrants,[1] was a rival Grand Lodge to the Grand Lodge of England. It existed from 1751 until 1813 when the United Grand Lodge of England was created from the two Grand Lodges. They are now called the Antients, in contrast to the Moderns, the original Grand Lodge who had moved away from the ritual of Scotland, Ireland, and now the Antient Grand Lodge. This Grand Lodge was also informally called the Atholl Grand Lodge because the Third and Fourth Dukes of Atholl presided over it as Grand Masters for half of its 62-year existence.[2]

Apron of the Moderns Grand Lodge

Apron of the Moderns Grand Lodge, ca 1790, from the Library and Museum of Freemasonry, http://www.freemasonry.london.museum/catalogue.php

Michel and Jane’s fifth child (of nine) was born in London. The sixth, Humphrey, Jon’s direct ancestor, was born in Scotland in 1821. Why he was born there is unclear. According to Jon’s notes on a Family Sheet (NY Davis) for Michel Davies, the family arrived in New York City on June 24, 1823 aboard the ship London from London. At the time of their arrival, Jane Davies (Davis) would have been about 31 years old. She would have brought her seven children, born within the previous eleven years.

On the London’s passenger records, a Philip Harris, 25, is listed after the Davies family. He would most likely have been related to Michel Davis’ wife, Jane. They were among New York’s small Sephardic community. Jon located the tombstone of Sarah Davis in the Spanish and Portuguese Cemetery on 21st Street in New York City. In this location, the first burial took place in November of 1829. Jane died in March 1830.

Jon traced Michel’s early years in New York. His profession was listed as glasscutter, grocer (which had a much wider meaning at that time), the sale of dry goods of all types) and segars [sic].

It is interesting to note that although Jane was buried in the Spanish and Portuguese Cemetery, and that many of the Jewish families in New York at that time were Sephardic, Jon’s DNA test from 2000 showed no Sephardic dna. This could be because they were Ashkenazim, or because the Sephardic ancestry was so far back that it was not traceable through DNA.

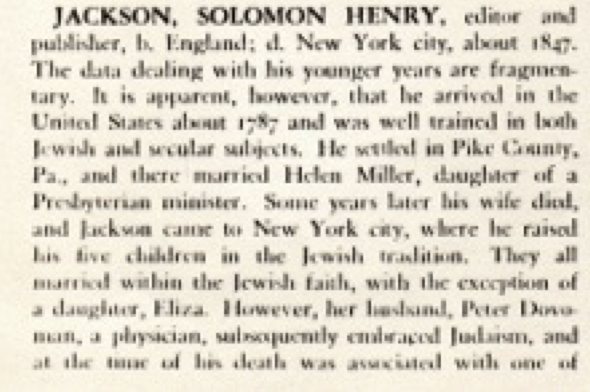

Some of the most challenging research to be found in the files is that on the Jackson family. Jon learned that his great-great-great grandmother, the mother of Jane Harris Davies (Jane was the mother of Humphrey Davis), was a Jackson. Her first name is not known.

Jon suspected that her brother would have been Solomon Henry Jackson, a relative of Daniel and Joseph Jackson. This was an extraordinary family, one connected to many prominent early American Sephardic families. Jon went on to donate the research on this branch for Malcolm Stern’s First American Jewish Families. The volume also included the Goldschmidt and Oppenheimer branches of his tree.

Malcolm Stern’s book; Jon Stedman’s family, page 238

Solomon Henry Jackson was probably a relative of Jacob Harris’ wife.

Among the many distinguished Jackson relatives was Rebecca Esther Jackson, the wife of Mordecai Manuel Noah.

DNA

Today there over a million samples of DNA in the database of familytreedna.com. The company was founded in early 2000. Jon Stedman was #68 to be tested.

An early analysis of Jon’s DNA.

Today much of the testing is performed for autosomal DNA, which allows for identification of people related on all branches of a family tree. https://www.familytreedna.com/products/family-finder The earliest tests were for Y-DNA, identifying only the direct paternal relatives. https://www.familytreedna.com/products/y-dna. Among Jon’s papers is an email from September 5, 2000 in which Jon writes that Bennett Greenspan, the found of Familytreedna, indicated he was the first “cold match”. Was Jon really the first match of the now-popular commercial DNA testing?

DNA Lecture

Lecture on Jon Stedman, one version of many, delivered 2016-2019

“The Stedman Story: Mystery, Intrigue, Adoption and DNA – Jewish Genealogy Strategies Unravel a Family Mystery”

What makes the story of Kelly unique, is that the adopted child was able to tell her birth mother her – the mother’s – complete family history. The birth mother had no information whatsoever on her ancestors.

This story began about six years ago with a call from Jan Meisels Allen. She received a call from the executrix of the estate of Jon Stedman. Jon, who lived in Denton, Texas but was born in Oklahoma, was the son of a John Stedman, a man who his son Jon learned late in life, was originally named Jesse Oppenheimer, a scoundrel with German Jewish roots who abandoned his first wife and three young sons in New York City, leaving them in debt, and set off to begin a new life with a new wife, Jon’s mother, in Oklahoma in the 1930s. Shortly after Jon’s birth, Jon’s father left him and his mother, and went married a third time. Jon rarely saw his father, who died when he was a teenager. Jon spent much of his adult life exploring the history and genealogy of his his father’s – and mother’s families.

Jon died in 2009 without heirs and without having published anything from his decades of research. The Executrix of Jon’s estate was looking for a person to arrange these research papers and write a book from more than 50 years of his work, and was offering a sizeable amount of money for this task. I agreed to take on the task, but Jan and I both thought that this work should be done only after a large portion of the funds was donated to several genealogy organizations including the Federation of Genealogical Societies. One of the beneficiaries was the IAJGS, the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies. Out of this funding came the John Stedman Award, named for Jon Stedman’s father, because Jon himself did not wish to be acknowledged directly.

One of the remarkable aspects of Jon’s research was his tenacity and drive. He had great curiosity, and when DNA testing was in its infancy, Jon had himself tested. He was #68 of the almost million people tested to date on FTDNA, having swabbed himself only a few months after the company started in business in spring 2000. At the time, the only test available was a 12 Y-chromosome STR. Bennett Greenspan, founder of the company, wrote to Jon a few months later that he was FTDNA’s first “cold match”.

The Familyfinder test was not even invented during Jon’s lifetime, so I had his sample retested in 2013, four years after his death. Soon after the results were posted, I received a call from Kelly Moore. She informed me that she was an extremely close match to Jon, but had been adopted, was looking for her birth mother, and was hopeful that the match would enable her to find her. Kelly had been working unsuccessfully for a decade, using the scant information that she was given in the papers she received when she was adopted.

Kelly would go on to meet her birth mother and her birth father, and their families, and unlike some stories in which a found birth child is unwanted, Kelly’s six half-siblings, parents and their spouses welcomed her into their lives.

Just how was Kelly related to Jon Stedman? John Stedman, Jon Stedman’s father, changed his name and also named four sons after himself. The first two sons, both named Jesse Oppenheimer, died. The third son, also Jesse Oppenheimer, lived, but his surname was changed to Palmer, his mother’s maiden name, after John abandoned the family in New York. John had two more sons from the first wife before he left for Oklahoma, and they also took the name Palmer.

Loretta, Kelly’s mother, is a daughter of the surviving Jesse Oppenheimer, by then Palmer. Because John Stedman abandoned his sons in NY, the next generation was told that their grandfather had died. Loretta, Kelly’s mother, did not know anything about John Stedman. When Kelly’s mother first asked, “How did you find me”, Kelly said, “Through Jon Stedman.” But Loretta had no idea who that was. And when Kelly asked, “How does it feel to come back?”, Loretta asked “what do you mean?” Loretta was a vice president of her synagogue, but had no idea when she converted to Judaism prior to her marriage, that her ancestors had been Jewish.

What all of us did not know—until we figured it out when we pieced the story together very recently, was that John Stedman, for whom our IAJGS award is named, was a bigamist, not divorced from his first wife when he moved to Oklahoma and married Ardath Tolson.

Conclusion

It’s hard to underestimate Jon Stedman’s tenacity and curiosity. He was a pioneer in in DNA and testing. He strove to understand every new technology and use it. He was generous with his time, working with Malcolm Stern on his book and assisting dozens of researchers in their work. Family history was his passion. He could not possibly have known in his lifetime that he would be remembered not only for his research, but also for his DNA test that changed the life of his adopted half-great-niece Kelly and her family; for his estate that was used to found the John Stedman Award of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies, for his work that would be so appreciated by cousins worldwide. His estate also endowed awards and programs in other genealogy societies, and in Denton, Texas.

According to Dayonne Work, Jon was not interested in having his collection put into an online database on Ancestry or elsewhere, but he did want his research to be accessible. With the passage of time, many others have input or duplicated his work, and the trees are available all or in part on many of the major genealogical databases. But even now, the depth of Jon’s thorough research stands as a testament to what could be accomplished at a time when online resources were more limited. His files contain documents that could be obtained only with hard work, lots of correspondence, decades of perseverance, and a very good mind.

Jon’s research papers may be found in the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio.

http://americanjewisharchives.org

Inquiries may also be sent to karenfranklin@gmail.com

Karen S. Franklin is director of Family Research at the Leo Baeck Institute, a library and archive of German Jewish history. A past president of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies, she is the recipient of its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019.